- Home

- Simon Brading

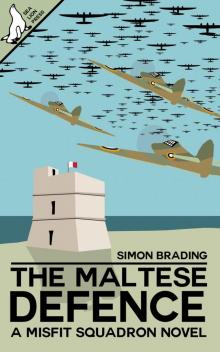

The Maltese Defence

The Maltese Defence Read online

The Maltese Defence

A Misfit Squadron Novel

January 1941 - May 1941

Simon Brading

Cover artwork by Jack Tindale

Misfit Squadron badge by Ian T. Brading

This book is a work of fiction. While ‘real-world’ characters may appear, the nature of the divergent story means any depictions herein are fictionalised and in no way an indication of real events. Above all, characterisations have been developed with the primary aim of telling a compelling story.

Published by Sea Lion Press, 2019. All rights reserved.

For the James who inspired me to become what I am and the one who brightens my future.

The Misfits

A Flight - Turn Fighters

Badger One - Abigail “Abby” Lennox. Pilot of Dragon.

Badger Two - Gwenevere “Gwen” Stone. Pilot of Excalibur.

Badger Three - Bruce “Walkabout” Walker. Pilot of Sable.

Badger Four - Montgomery “Monty” Fletcher. Pilot of Raptor.

B Flight - Interceptors

Badger Five - Derek “Twitcher” Niven. Pilot of Swift.

Badger Six - Kitty Wright. Pilot of Hawk.

Badger Seven - William “Mad Mac” MacShane. Pilot of Jaguar.

Badger Eight - Chastity Arrowsmith. Pilot of Dove.

C Flight - Support

Badger Nine - Owen “Sheepish” Llewellyn. Pilot of Bloodhound.

Badger Ten - Wendy “Firepower” Llewellyn. Pilot of Dreadnought.

Badger Eleven - Charles “Chalky” Isaacs. Pilot of Vulture.

Badger Twelve - Ophelia “Scarlet” Flynn. Pilot of Hummingbird.

Prologue

11th January 1941

When the air raid siren wailed, the pilots were just finishing their breakfasts in one of the underground ready rooms of RAC Hal Far, near the southernmost point of the island of Malta. As one, they checked the chronographs attached to the wrists of their blue Royal Aviator Corps flightsuits before lifting their heads and grinning at each other. There was a heartbeat’s pause, then twelve voices called out buon giorno, Italia! with the same cadence - that of the woman from the Imperial Italian radio station who took over at seven in the morning, precisely the same time as the Italian Air Force, the recently renamed Legione Aerea, launched their first raid of the day. A week earlier, that wireless station had been the only one they could get, but then, to everyone’s relief, a technician at RAC Luqa had cobbled together a more powerful receiver, capable of receiving the Global Service from the repeating station at Gibraltar. The signal was intermittent and was often lost altogether if the weather was bad, or even just if the wind was in the wrong direction, but it was better than the propaganda and patriotism spouted by the state-controlled Italian station.

‘This is the KBC Global Service, speaking to you from London. Here is the news at the top of the hour...’

The pilots continued with what they were doing, ignoring the siren and barely listening to the static-laden voice coming from the tannoy speaker in the corner of the room, knowing that nothing would be said that could possibly affect them, isolated as they were from the rest of the world not only by distance, but also by design of the enemy.

After three cycles of the siren, it faded to nothing, like an aircraft flying into the distance, and still the men and women didn’t stir.

On any other British fighter base, the siren would have prompted the pilots to leap out of their seats and race for the door, spilling their tea, tossing newspapers and bacon sandwiches aside, and scaring nearby pets, and it would have done on Malta, where the enemy bases were only sixty miles and twenty minutes of flying time away, if it weren’t for the fact that the Italians insisted on still using airships. The antiquated and obsolete machines took almost an hour and a half to make the crossing from Sicily and the Italians liked their entire raid to arrive together, which meant that the British pilots had plenty of time after the enemy aircraft were spotted before they needed to take off.

The pilots weren’t able to sit idly for long with the prospect of a hard fight so near, though, and they soon began to finish up and drift out of the room.

Eventually, there were only two left - a handsome young man with light brown hair and a striking blonde woman with a gap in her ready smile - the same two who lingered every day and who had learnt through extreme hardship to appreciate any chance they had to be alone together.

As Drake considered his next move, he reached across the chess board to take Tanya’s calloused hand in his. He ran his thumb across the simple Duralumin band on her finger that he’d had one of the fitters fashion for them, feeling the weight of the identical one on his own.

There was no need for them to say anything. After two weeks of three sorties a day everything had already been said too many times. They knew they were pushing their luck, that one day, perhaps that day, one, or both of them, wouldn’t come back, but neither of them were going to shirk their duty; they had long since reconciled themselves to the possibility of meeting the Dark Scythesman and had cheated him with a smile on several occasions. All that remained, then, was to appreciate the moment, take their fill of each other, then make sure they did what they had to do, to the best of their abilities, no matter what it cost them.

Drake frowned at the board. He’d taught Tanya to play chess soon after they’d arrived on Malta as a way to pass the time between sorties. She had proved to be a very quick study and, although she knew nothing about any of the openings which had been developed over centuries, she managed to improvise her own. They didn’t always work, but when they did, they worked spectacularly well.

It seemed that morning’s game was going to be one of those occasions when she wiped the floor with him and he had to accept that defeat was inevitable. He laid his king down and looked up from the board to give Tanya a wry smile. ‘Congratulations. Again.’

He stood and offered her his hand. ‘Shall we?’

She allowed him to pull her to her feet, but then surged forwards to take him into her arms and pushed him into a few dance steps.

He looked at her in surprise. ‘I didn’t know you could dance.’

‘Of course! I taught ballroom dancing in Moscow and when we get to London you’re going to take me to plenty of balls so that we can show off together.’ She winked. ‘I might even let you lead every so often.’

Drake found himself twirled round before he even knew what was happening and laughed as she tugged him towards the door.

Lord Rudyard Sebastian Augustus Cholmondeley Drake, Rudy to his friends, had only arrived on Malta recently, in the early hours of the 26th day of December, what had previously been called Boxing Day, under extremely unusual circumstances - he had escaped from “Bertha”, the airship which was home to the elite Prussian squadron “The Crimson Barons”, but which also served as a prisoner of war camp for captured pilots, by jumping through a hole in its hull created by jettisoning one of its enormous springs and using powered glidewings to fly to the island.

A ragtag bunch of escaped prisoners of war had made the perilous journey with him, including his fiancée, Tatiana Guseva, a pilot from the infamous Muscovite “Wolfpack Squadron”. The rest - a Norwegian, a Pole and three other Muscovites - had since been ferried to a Muscovite port in the Black Sea by undersea boat, wanting to rejoin the fight against Kaiser Wilhelm III in their own countries, but Drake and Tanya had volunteered to join the fighter squadron defending the island, the so-called “Hal Far Fighter Force”.

Sky Commodore Lloyd Hughes, the Commanding Officer of the RAC forces on the island, which included not only the fighter squadron, but also four bomber squadrons based at RAC Luqa and RAC Ta’Kali, had sent their request to London, along with Drak

e’s report on the airship, Bertha, and the Prussian plans for Malta.

It would take a while for a reply to come from London - the message had to be taken by undersea boat as far as Gibraltar where it would then be transmitted - but the two pilots were desperately needed, so they immediately began flying with the squadron.

An undersea boat brought back an answer from Sir Douglas Pewtall, the Commander of the Royal Aviator Corps a week later. It not only assigned them to the squadron, but also granted Tanya a commission as an aerial officer and informed Drake that he was promoted to squadron leader, placing him in command of it. When Drake protested that he had only just arrived, Hughes explained that, not only was he already the highest-ranking pilot, but he was by far the most combat experienced, the others having been mostly transport or Naval flying boat pilots before the Italian offensive began.

Drake’s new command comprised of six MK1 Hawking Harridans, four Cheltnam Sea Centurions - ageing biplanes on “permanent loan” from the Navy - and two curious, hand-crafted aircraft, built and flown by local aviation enthusiasts. Originally there had been twelve Harridans, delivered by the HMS Arturo in August, just before the carrier had headed north to take the Misfits to Muscovy, but three had been destroyed outright and three more had been cannibalised just to keep the remaining aircraft in the air.

It was a pitiful force when compared to what had defended Britain against the might of Die Fliegertruppe so recently, but it had managed to hold back the Italian assault for six months.

It wouldn’t be able to do so for much longer, though, because the aircraft were on their last legs.

Due to the difficulty of getting convoys safely to the island, stocks of everything were running out. The only supplies actually coming to the island were smuggled in by fishermen or brought by the occasional undersea boat that had had occasion to visit Alexandria or Gibraltar, but they were paltry at best. Food stocks were getting low and luxuries (including tea, to the horror of every Brit on the island) were non-existent, but more importantly ammunition had almost run out and there was nothing left with which to repair the aircraft and there wasn’t a single one that didn’t have some damage or other. That didn’t stop the pilots flying, though; the bombed-out ruins of the houses they flew over each day was a testament to how important their job was, even beyond any strategic considerations King George VI and his government might have.

Drake stood on the airfield, shading his eyes against the bright morning sun to inspect his squadron. It was not a particularly impressive sight.

The Centurions were in decent shape, but had been outdated even before the start of the war. They were slow and armed with only four .303 machine guns, but they did, however, have extremely tight turning circles and their pilots had learnt to use that to full advantage and had made a good few kills. They had wooden frames, covered by coated or “doped” linen, which meant that it was easy enough to get them back into the air after sustaining damage, but they’d been repaired so many times that the stocks of fabric had run out and most of them now had patches of red and white checks, betraying the fact that they had been mended using tablecloths, bought in bulk from a local manufacturer.

The Harridans weren’t nearly as well off. They had been designed for ease of repair, and they were, but it didn’t matter how easy it was if there was nothing to repair them with. Spares, including those provided by sacrificing three of them, had run out weeks ago and they were worn out. They looked it, too, with dozens of patches to show where damage to the Duralumin skin had been hastily covered with salvaged metal.

As for the two Maltese aircraft...

Drake wandered over to the colourful machines.

Like the Misfit Squadron aircraft, the pilots of the Maltese aircraft had designed and constructed their own machines, but unlike the Misfit aircraft, the Maltese ones weren’t exactly state of the art.

Without access to the latest materials or construction methods the pilots had drawn on the traditions of their people for the designs and used whatever they had at hand to create machines that were best described as unique. That didn’t mean that they weren’t ingenious or effective, though, and the pilots had shot down their fair share of Italian aircraft.

The aircraft piloted by Spiru Felice, a small man with round spectacles and a permanent smile, resembled nothing more than a Luzzu, the Maltese fishing boats that could be seen off of the coast each day, although it was much narrower, designed as it was to slip through the air and not water. The fuselage was wood and ribbed like a boat, the front flat and beaked like the prows of the local vessels. The wings and tailplanes were canvas over a wooden frame and shaped like triangular lateen sails. The canopy was glass and metal and it stuck up from the fuselage, giving Felice impressive all-round vision. It was brightly painted, like the fishing boats, with blue on the bottom and yellow on top and there were two eyes on the prow, just behind the airscrew. All in all it was a strange creation that was more likely to provoke laughter than admiration, but Drake had seen it more than hold its own against the aircraft the Italians were throwing against them, especially since Felice was one of the most talented pilots he’d ever seen.

The aircraft belonging to Anton Baldacchino, a dark-haired and intense man with movie star good looks, was also nautically themed, but his at least looked like it belonged in the air and not bobbing up and down in the gentle waves of the Mediterranean Sea. It was triple-hulled, like a trimaran, making it look vaguely like Kitty Wright’s Hawk, except that the central hull, where the cockpit and two large-calibre machine guns were situated, was the longest of the three and the others were just large enough to hold springs with their corresponding airscrews. The single tailplane on the central hull, much smaller than the one on Hawk, made it far less manoeuvrable than the American’s aircraft, but with its twin springs and lightweight construction, also of wood and canvas, it more than made up for that deficit with sheer speed. It too sported eyes on its nose and was also brightly painted, although in red and blue, with a line of green dividing the colours.

Both machines had originally been powered by antique A.74 FIAM springs, imported from Italy before the war, but they had been replaced with much more modern Fischer-Berg FB601’s, salvaged from enemy aircraft that had crashed on the island, improving their performance considerably.

Despite having sustained just as much damage in the hard fighting as the British aircraft, the two machines were spotless and freshly painted. That was because, while the British had limited resources and only a small team of fitters who had trouble just doing enough to keep their machines in the air, the Maltese had a small army of volunteers, mostly fishermen and their families from all around the island, who appeared from nowhere after every sortie. Proud that their countrymen were fighting for the freedom of their island alongside the British, the men, women and sometimes children, not only donated their time, but often brought along the materials that were needed, all of them readily available. They used the techniques they used on their boats, techniques that had been handed down over generations, to extremely quickly repair the aircraft, turning them around in minutes - even faster than they could be rewound and reloaded.

Usually Drake had no reason to speak to any of his pilots before takeoff; he could trust them to take care of themselves and their machines, just like those of any more conventional squadron, but that day there was something very different about the two Maltese aircraft and he felt he just had to ask about it.

The two pilots were standing together between their machines with a group of locals. They looked tired, but happy, and turned to grin at Drake when he approached.

Felice and Baldacchino snapped smartly to attention and saluted. Drake returned it out of habit, even though he liked to keep things more informal, especially among those pilots who weren’t strictly under RAC discipline.

‘As you were, gentlemen.’

Once the men had relaxed, he nodded in the direction of Felice’s aircraft and raised an eyebrow. ‘Interesting modificati

on.’

The grins on the faces of the Maltese pilots just widened as Felice replied. ‘Well, my Lord, we’ve been thinking about our airship problem.’ The Maltese pilots insisted on addressing Drake by his title, no matter how much he tried to get them not to. ‘And we thought we would try to do a little fishing.’

Baldacchino nodded enthusiastically. ‘It is what we do best, after all.’

The Italian airships were relics left over from the First Great War. They were nigh on indestructible, requiring an inordinately large amount of concentrated fire to bring down and the British squadron just didn’t have the ammunition to spare. It wasn’t really worth the trouble anyway, because they carried quite a small payload compared to a modern bomber, so Drake had ordered his pilots to ignore them and go for juicier targets, such as the medium bombers. That didn’t mean he wasn’t keen to knock them out of the sky, though, and he was ready to listen to any idea as to how to do so.

Drake wandered over to the colourful fighter and bent down to peer underneath it. A ten foot length of metal with a sharp point and serrated edges ran along the keel of the aircraft. It was attached to a winch that had been embedded in the fuselage, just in front of the spring, so that it could be lowered in flight.

Drake looked up at his pilots. ‘A harpoon?’

‘A whale harpoon.’

Drake chuckled. ‘Appropriate.’ He stood up and brushed his hands off on his flightsuit. ‘I take it this is supposed to rip through the gas bags?’

Both pilots nodded, their grins firmly in place.

‘What happens if it gets caught in something?’

Baldacchino bent down and pointed to a complicated looking series of knots just above the ring of the harpoon. ‘If it doesn’t cut through and come away, we’ve rigged it so that a sudden jerk will detach it.’

The Lion and the Baron

The Lion and the Baron A Misfit Midwinter

A Misfit Midwinter The Russian Resistance

The Russian Resistance The Maltese Defence

The Maltese Defence